Your Cart is Empty

Menu

-

- Shop by Type

- End of Line Sale Items

- New In

- Viking Gifts Under $40

- Hand Forged Axes

- Silver Viking Jewelry

- Stainless Steel Jewelry

- Cremation Jewelry

- Necklaces and Pendants

- Hand Carved Wooden Pendants

- Kings Chains

- Viking Drinking Horns

- Pendant Chains

- Rings

- Bracelets

- Earrings

- Beard Beads and Beard Rings

- Collectables

- Ceramic Mugs

- Street Wear

- Horn Jewelry

- Bronze and Pewter Jewelry

- Shop by Theme

- Viking Axe

- Celtic Jewelry

- Dragon or Serpent

- Viking Raven

- Wolf / Fenrir

- Rune Jewelry

- Odin Jewelry

- Ram / Goat

- Shieldmaidens / Lagertha

- Sword, Spear or Arrow

- Thor's Hammer / Mjolnir

- Tree of Life / Yggdrasil

- Helm of Awe / Aegishjalmur

- Triquetra or Triskelion

- Valknut / Knot of Slain

- Vegvisir / Viking Compass

- Veles / Bear

- Blogs

- Help

-

- Login

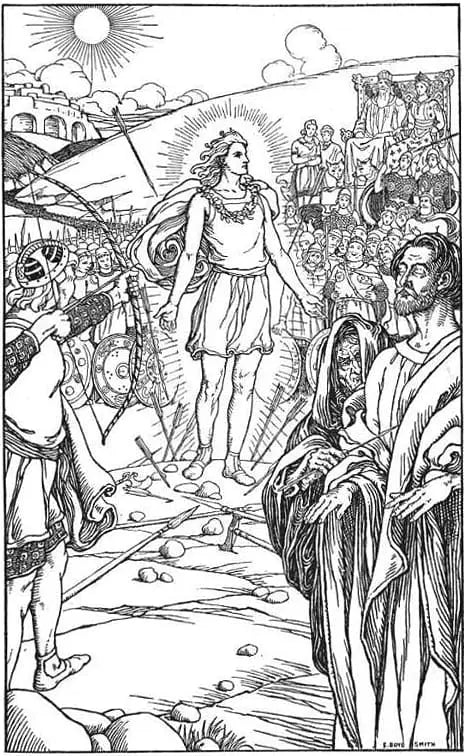

Baldr

Baldr is a Norse deity whose role in mythology is much disputed. He is referred to in the myths as the most beautiful of all the Aesir and the son of Odin and Frigg. Together with his wife Nanna, he has a son, Forseti. His residence is Breidablik. Baldr is commonly described as the god of justice.

The myth of Baldr's death is among the best known in Norse mythology, and it is retold or referenced in several other tales. In the myth, Baldr is killed by an arrow made of mistletoe shot from his brother Hodr.

His mother had sworn all the things in the world would never harm him. Only the mistletoe she had found so harmless that she did not think it necessary to swear to it.

In Norse mythology, Baldr is presented more as a passive god than an active one, but he is nevertheless given a central place in the great cosmological saga by several scholars since his death marks the beginning of the events leading to the end of the world. After Ragnarok, Baldr will return from the underworld.

Etymology

The origin of the name Baldr is uncertain, but it has been suggested that it means "the shining one" or "the lord". Jan de Vries thought that his name meant "the brave one", but this has since been rejected as it does not make sense in the context of the known myths. Images on bracteates from the Iron Age possibly show Baldr being struck by the mistletoe, which may be an indication of the myth.

Characteristics

In the mythological works of the Icelander Snorri Sturluson, Baldr is depicted exclusively as a good and pure, but also passive god. Snorri's description includes this: "There is nothing but good to say about him. He is the best, and he is praised by all. He is so glorious and bright of aspect that it shines around him, and the whitest of all grasses is compared to the eyelashes of Baldr.

Hence you may have an idea of his handsomeness, both in hair and figure. He is the wisest of the Aesir, the gentlest, and the most eloquent. But his nature is such that none of his precepts can be observed.

In the Edda poems, which were Snorri's main source, however, there is evidence that Baldr also had a more warlike duality, for example in the poem Lokasenna, where Frigg says that Loki would hardly have escaped the hall alive if her son Baldr had been present. This is also supported by kennings in shield poems, as more warlike names such as Army-Baldr, Spear-Baldr and Battle-Baldr appear in them.

Baldr appears in another myth from Snorre's Edda, when he once became the object of Skade's affection and she wanted him for a husband.

The Norwegian religious scholar Gro Steinsland finds no evidence of an actual Baldr cult. She bases this assumption primarily on the fact that we know of no place names that can be linked to him with certainty.

Baldr's death

The meaning and origin of the myth of Baldr's death has always been and still is very controversial. Consequently, there is no commonly accepted explanatory interpretation.

The myth is not known in its entirety from a single source, but parts of it are told or referred to in several different sources, including Baldr's draumar, in which the dream that foretells his imminent death is the central element; Gylfaginning, which tells of the killing, how Odin tries to bring him back from Hel and his pyre Völuspá, in which the killing is the decisive turning point in the larger cosmological story of the fate of the world; and various references to the myth in Varftrudnismál, Lokasenna and the shield poem Húsdrápa, among others.

The myth consists of a series of episodes. The first begins with Baldr having nightmares that foretell his imminent death. In the poem Baldr's Draumar, Odin addresses the prophecies by riding to Hel to question a seeress about their meaning. He is told that fate is inevitable and that Ragnarok will follow Baldr's death.

In Gylfaginning (48) Baldr's dreams are also mentioned. Here the gods responded by Frigg taking an oath that fire and water, iron and ore, stones, earth, trees, diseases, animals, birds, oaths, worms would do no harm to Baldr.

But Loki noticed that only the mistletoe had not sworn not to harm Baldr. The mistletoe is a parasitic plant, and in Völuspá it acts as a death symbol growing on Yggdrasil. Loki then tricked Hodr into shooting the mistletoe at Baldr, who fell dead when it hit him.

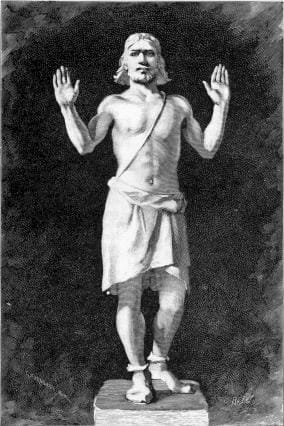

This is the greatest deed of misfortune done among gods and men. While the gods buried Baldr on his ship Hringhorni, Hermod rode to Helheim to get Baldr back. When Baldr's body was put on the pyre, Nanna's heart broke and she died.

She was then laid by her husband's side in the ship. Odin gave his ring Draupnir as a burial gift. It is said that the gods needed the help of the giantess Hyrrokin to push Baldr's ship into the water, which even Thor was unable to do.

By this time Hermod had reached Helheim, where Hel promised to let Baldr return if all the world would weep for him. The only one who refused was the giantess Tøkk, and Baldr had to stay in Helheim.

In the poem Völuspá it is stated that Baldr will return after Ragnarok and that he will be reconciled with Hodr. However, the myth does not end with Baldr's death, as such a killing would have to trigger a blood revenge.

Since the killer, Holdr, was himself of both Baldr's and Odin's own lineage, the avenger could not be of the same blood, and therefore it had to be the child of a giantess. By deception Odin succeeded in impregnating Rindr, who bore the son Vali, who one night killed Hodr.

The other instigator was Loki, and the poem Lokasenna tells how the gods expelled him from their circle. Though he hid, he was captured by the gods, who bound him until Ragnarok.

Saxo Grammaticus Version

Saxo's story of Hotherus (Hodr) and Balderus (Baldr) in Gesta Danorum is, by virtue of the coincidence of the main characters' names, a parallel to Snorri's and the Edda version; but there are so many differences between them that they can only with difficulty be understood as the same story. The main difference is that Balderus appears as the villain, and is an active participant in the struggle between Hotherus and him.

This struggle is also presented as a war between two groups over a woman. In Saxo's story, Balderus is invulnerable, as in Snorri, but is nevertheless killed by Hoetherus with a magic sword. As in the Icelandic version, Balderus is taken to Hel and avenged by a son Odininus (Odin) has with Rinda.

The background to these two parallel versions is unknown. Anders Bæksted speculates whether Saxo's version is either based on an otherwise lost East Norse tradition, or whether he composed his own story on the basis of an incomplete transmission of the Icelandic version.

Other versions

Lejrekrøniken, which is probably older than both Saxo's and Snorre's works, contains a short euhemerised story about the Saxon king's son Hother (Hodr) and King Haddings' daughter. It is said that Hothbrod first killed Othen's (Odin's) son Baldr in a battle, and then drove Othen and Thor away. Finally, Hothbrod was killed by Othen's son. The story concludes with the information that Hother, Othen, Balder and Thor were later mistaken for gods.

The Swedish religious scholar Birger Nerman has suggested that the story of the brothers Hæðcyn and Herebeald, who appear in Beowulf, is based on the myth of Hodr's killing of Baldr. But Liberman finds this unlikely, since apart from a certain similarity in the names of the brother-killers, there are no similarities between the two tales.

Interpretations

Gro Steinsland has identified two traditional models of interpretation of the Baldr myth. According to one, Baldr's death has been related to the mythology of Odin as god of war.

The Dutch linguist Jan de Vries, for example, has suggested that the myth was linked to an initiation rite, in which the young warrior is initiated into Odin by undergoing a mythical death, and then resurrected as Våle. I.e. it belonged to the Valhalla representations, where the warrior after his death was resurrected as a member of Odin's army.

Another prominent representative of this tradition is the English philologist Gabriel Turville-Petre. In the second, Baldr was interpreted as a dead and resurrected fertility god. Within this tradition, he is often compared to Middle Eastern deities whose death was a dramatisation of the changing of the seasons through a cult drama, such as Baal, Tammuz and Adonis.

Prominent representatives of this tradition include Gustav Neckel and Frands Rolf Schröder. Steinsland, however, finds serious problems in both models.

For example, it is difficult to link Baldr with the distinctly warlike Valhallaian logic, as long as he is explicitly portrayed as a peaceful and passive god.

On the other hand, she does not believe that Baldr cannot be linked to the seasons, since he does not return from death until after Ragnarok, when a whole new world has emerged.

Anatoly Liberman even believes that such a comparative explanation does not make sense if it is not grounded in the local religious system where the myth was told.

In his interpretation of the Baldr myth, Frederik Stjernfeldt has characterised Baldr as a scapegoat, thereby making him a passive victim of Loki's machinations.

This interpretation means that Loki in fact becomes the myth's real protagonist. On the basis of a structuralist analysis, Jens Peter Schjødt also interprets Loki as a figure who is essential to the understanding of the myth.

He represents fate, which the Norse saw as the main driving force in their lives. John Lindow characterizes the death of Baldr as the central episode in the cosmic struggle between the gods and the giants.

More recently, the Russian philologist Anatoly Liberman has suggested that the story of Hodor's killing of Loki is a relic of an older mythology in which Baldr was seen as the god of the sky and protector of life and light, while his brother Hodor was the god of the underworld, who in some areas may have been identical to Loki.

He believes that Saxo's and Snorre's versions are the result of adaptations in which fragments of the original myth have been combined with other mythological material.

He also believes that the mistletoe was not originally part of the myth, as this plant was unknown in the North in ancient times. In his opinion, it was more likely to have been horsetail.

Baldr and Christ

Sophus Bagge suggested in 1881 that the description of Baldr in Gylfaginning was inspired by the Christian legends about Jesus. One of the arguments for this comparison is that Baldr was referred to by Snorri as "the whitest of the Aesir", which has thus been characterized as a parallel to the Norse name for Jesus, White Christ.

Other similarities that have been drawn are their role as suffering and good gods who die as innocents, just as Christianity's dualistic struggle between good and evil has been rediscovered in the conflict between Loki and Baldr. However, this comparison is highly contested.