Your Cart is Empty

Menu

-

- Shop by Type

- End of Line Sale Items

- New In

- Viking Gifts Under $40

- Hand Forged Axes

- Silver Viking Jewelry

- Stainless Steel Jewelry

- Cremation Jewelry

- Necklaces and Pendants

- Hand Carved Wooden Pendants

- Kings Chains

- Viking Drinking Horns

- Pendant Chains

- Rings

- Bracelets

- Earrings

- Beard Beads and Beard Rings

- Collectables

- Ceramic Mugs

- Street Wear

- Horn Jewelry

- Bronze and Pewter Jewelry

- Shop by Theme

- Viking Axe

- Celtic Jewelry

- Dragon or Serpent

- Viking Raven

- Wolf / Fenrir

- Rune Jewelry

- Odin Jewelry

- Ram / Goat

- Shieldmaidens / Lagertha

- Sword, Spear or Arrow

- Thor's Hammer / Mjolnir

- Tree of Life / Yggdrasil

- Helm of Awe / Aegishjalmur

- Triquetra or Triskelion

- Valknut / Knot of Slain

- Vegvisir / Viking Compass

- Veles / Bear

- Blogs

- Help

-

- Login

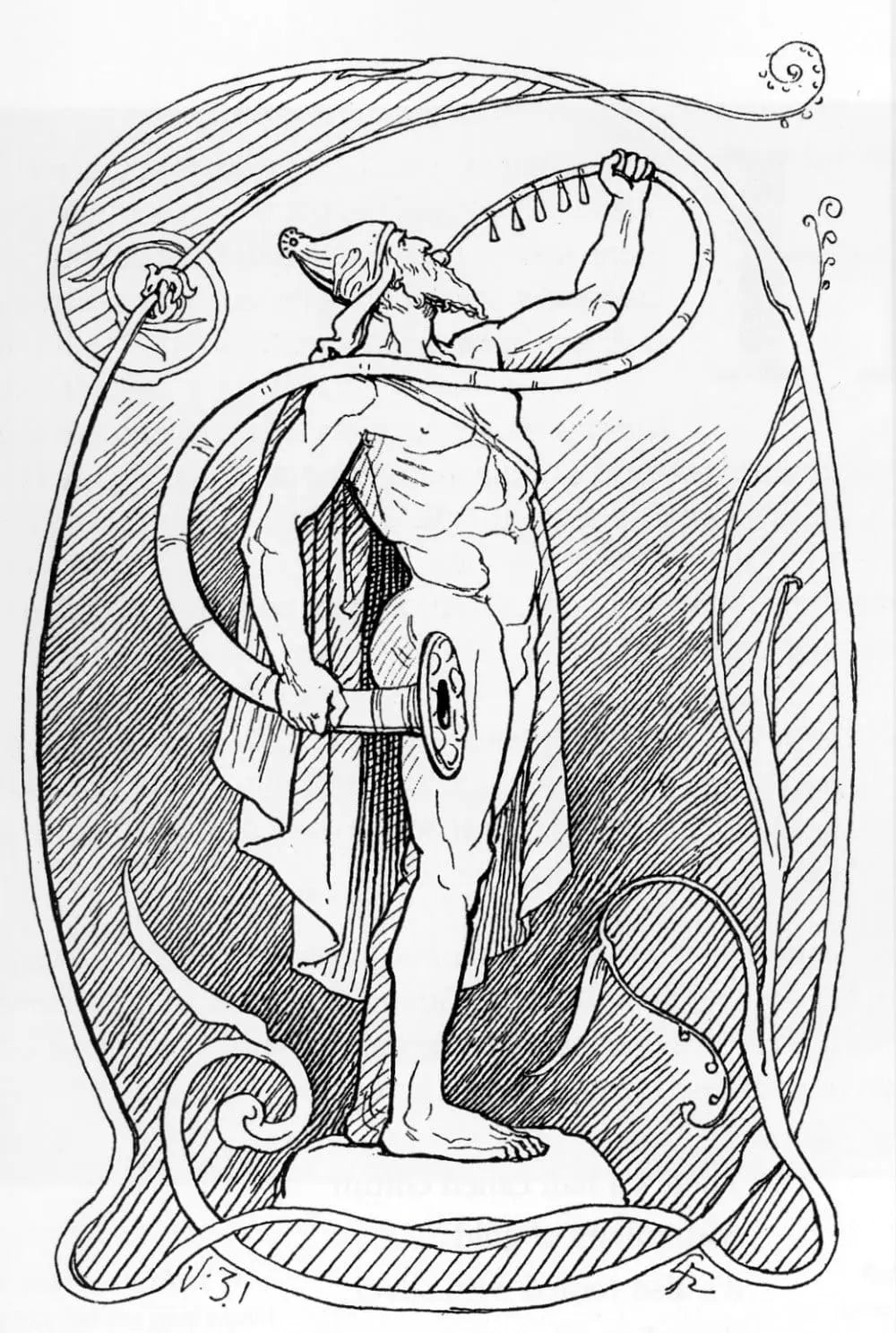

Heimdall

Heimdall is one of the most enigmatic gods in Norse mythology. Given his amazing eyesight and hearing, he appears in the myths as the guardian of the gods, sitting at the end of Bifrost and making sure no giants sneak into Asgard.

At Ragnarok, he blows the Gjallar horn when the giants attack, so the rest of the gods and heroes can prepare for battle. According to Vølven, in the final battle he will fight Loki.

They will end up killing each other, but Heimdall will still be the last of the gods to die in Ragnarok. He was born in primordial times at the edge of the world to nine mothers.

Several theories have been put forward about his function and origin, for example he may have been an ancient sun or moon god, a personification of the world axis, the progenitor of man, or even the ruler of the world that will rise after Ragnarok.

Parallels have also been found in other mythologies, for example in the Sami world god Varalden Olmay and in Celtic-Irish folklore and mythology. The Norwegian religious scholar Gro Steinsland has even suggested that Heimdall may be the result of a fusion of different traditions.

There are no remains, either in the written sources or in the archaeological and topographical material, that point to a religious worship of Heimdall in the Viking Age. This may mean either that he is a very old deity who had lost his importance, or that he had never been the centre of a cult.

Characteristics and Function

Based on the fragments of myths about him that have been handed down, Heimdall's function and character appear very unclear. Steinsland describes him as the most enigmatic deity, appearing in the myths as distant and exalted. To her he seems like an old god who was reborn in the Viking Age.

She believes that he is more connected to the cosmic dimension, space and time, and to humanity as a whole, than to everyday life, like some of the other better-known gods. Snorri Sturluson's texts contain a number of details about Heimdall, some of which cannot be found in the known myths.

Together with the many enigmatic skaldic references, this suggests that there were several lost myths about Heimdall, such as one explaining why a sword can be called Heimdall's head and vice versa.

The sentinel of the gods

In the myths passed down, he is given special attributes and possessions related to his function as a sentinel. His hearing is exceptional, he can listen to the grass sprouting and the wool growing on sheep. He is able to see 50 miles away and equally well day and night. And he didn't need more sleep than a bird every night.

His dwelling is called Himinbjörg, and it lies where one end of the Bifrost bridge is attached. It is the bridge between Asgard and Middle-earth. The red in the bridge is burning fire. No one could get past Heimdall undetected, and the gods put him to guard the bridge so that no giants would cross it.

His horn is called the Gjallarhorn, and when it is blown, it can be heard in the world of humans (Midgard) and of the gods (Asgard), of the giants (Jotunheim), of the underworld (Hel) and of many other worlds, such as Vanaheim, Alfheim, Svartalheim, Niflheim and Muspelheim.

It is used to alert the gods when enemies threaten them. The signal from this horn will mark the beginning of Ragnarok, the end of the world. In the battle, Heimdall himself must face the devious Loki, the commander of the giants.

They will send each other to their deaths, like Thor and the Midgard Serpent or Odin and the Wolf Fenrir.

Loki's Enemy

Despite his function as guardian, Heimdall was not a warrior god. There is, however, one surviving myth with him as the protagonist that involves battle. In the shield poem Húsdrápa, there is a brief summary of Heimdall and Loki's battle for Freya's necklace Brísingamen.

The two were apparently sworn enemies and were also to meet at Ragnarok. The hostility was clear and perhaps something primal and constant between them. The Völuspá tells us that they will kill each other here.

Margaret Clunies Ross describes them at once as each other's opposite and parallel. She emphasises that they both live on the fringes of the gods' social sphere, though for different reasons: Heimdall as sentry, Loki whose loyalty is debatable.

The reason for Loki and Heimdall's enmity is not found in the extant source material, but Clunies Ross suggests that it symbolises their being in two diametrically opposed positions in the mythological system; Loki is to blame for the fall of the gods, while Heimdall is the ever-loyal watchman.

Birth of Heimdall

The edda poem Hyndlaljóð mentions a god born of nine giant sisters at the dawn of time, at the edge of the earth. This god is commonly known as Heimdall. Snorri quotes from an otherwise lost poem Heimdall to say himself: "Nine mothers' son am I, nine sisters' son am I."

Previously, the nine mothers were usually identified with the sea gods Aegir and Ran's nine daughters. They were a representation of the waves of the sea. However, in the poem Fjólvinnsmál, Njord is also assigned to nine mothers in the Song of the Sun.

His mothers may also be the nine giants mentioned in Völuspá verse 2, which would make him older than Odin. The number nine symbolizes wholeness in Norse culture, and collectives consisting of, among others, nine women are not uncommon in mythology.

In Hyndlaljóð his mothers are called Atla, Augeria, Aurgiafa, Egia, Gjalp, Greip, Jernsaxa, Sindur and Ulfrun. In another source it is mentioned that the names of Aegir's nine daughters were Himinglæva, Dufa, Blodughadda, Hefring, Ud, Hrønn, Bølge, Drøfn and Kolga. These names probably had a purely symbolic meaning, as they are all different words for the term "wave".

Heimdal's birth makes him unique: if he is the son of waves, it took place on the beach between the sea and the land, giving him a liminal status. But his status as the son of nine mothers alone makes him very unusual.

Ancestry was a crucial factor in Norse culture, and it was the lineage of the father that usually determined the individual's place in the social hierarchy. But in Heimdall's case, his father is never mentioned.

The poem Hyndlaljód shows that the mothers were giantesses and that they were sisters. Gro Steinsland believes that this underlines the fact that no man was involved in his conception, which places him in an extremely special position.

Margaret Clunies Ross speculates, contrary to Steinsland, as to whether there was possibly a father involved. Clunies Ross finds that there is a parallel with the unknown father in the poem Rígsþula, where he incognito becomes a father himself.

She suggests that it may be one of the two sea gods Aegir or Njord, who had an incestuous relationship with their own daughters. This makes him either a giant or a Vanir.

Hilda Ellis Davidson believes that there is a weak implicit link between Heimdall and the Vanir. This assumption is based mainly on supposed relations between Heimdall and the sea, and thus the underworld, to which the Vanir were strongly linked, as well as the fact that Heimdall appears primarily in myths in which the Vanir goddess Freya plays a role.

The origin of social classes

According to the Edda poems Rígsþula (in English The King's Journey), Hyndlaljóð and the first verse of Völuspá, Heimdall is also the ancestor of the human race, although he is not mentioned in connection with the creation of Ask and Embla.

Steinsland believes that the reason for this was that he was not seen as a creator of man in the bodily sense, but rather as a social being and builder of society.

In Rígsþula, for example, it is told how Heimdall, on a walk (under the name Rig) along the beach, comes to three different farms, and there sleeps with three different women.

This resulted in three sons, making him the progenitor of the communities of thralls, peasants and jarler (great men). The sons' names are a reflection of the group they represent:

- Þræl ("servant") he had with the woman Eda (great-grandmother) married to Ái (great-grandfather). Þræl married the woman Þír and together they became the sire of the servants.

- Karl he had with Amma (grandmother), married to Afi (grandfather). Karl married Snør, and together they became the sire of the men (peasants).

- Jarl he had with Móðir ("mother"), married to Faðir (father). Jarl married Erna, and together they became the sire of the earls, i.e. the aristocracy. Their youngest son was Konr. He became the father of many sons, one of whom was named Danp, and he was the first king of Denmark.

The poem ends with the god Rig himself revealing himself to the young Jarl and calling him his son. Jarl's youngest son is given the name Kon Unge, which is reminiscent of the word konnungr, meaning king. They are the only ones to be recognised by the god as his own offspring.

Margaret Clunies Ross interprets the poem's message as that the aristocrats are the god's only recognized and therefore legitimate heirs, hence they are also the only rightful inheritors of the divine gifts; e.g. odalism, runemagic and power.

However, she also believes that the poem probably originated late, as she thinks that the tripartite social order is probably a reflection of the Christian medieval tradition of the three estates, although the individual functions are not quite the same.

Gro Steinsland questions whether Heimdall was originally the protagonist of the myth. It is only in the prose introduction that he is identified with "Rigr", and nowhere in the poem itself.

She finds that the character of the "Rigr" figure is in fact more like what one might expect of Odin than of Heimdall. She suggests that the identification in the introduction may be the result of a misunderstanding, arising from the idea of Heimdall as man's progenitor.

Heimdall and Ragnarok

When Ragnarok begins, Heimdall must blow the Gjallarhorn to warn the Aesir. Later, he must face Loki himself in a battle where they both fall. This gives him an important eschatological role, heralding the end of the world with his horn. This may be a parallel to the archangel Michael.

When Loki and Heimdall are dead, Surt lets his fire blaze so that the earth perishes, i.e. Heimdall represents the gods' last resistance before the end. It has been suggested that the idea of Ragnarok is influenced by Christian traditions such as the death of Balder and the horns of Heimdall, but many elements suggest that the idea of doom has ancient roots in Norse religion and that the role of Heimdall is an original Norse tradition.

Another indication of Heimdall's possible function as a god of social order is that Ragnarok in Völuspá begins after a time when the kinship community has disintegrated.

Just as Ragnarok was the overall result of a feud between the Aesir and the Giants that was marked by oath-breaking and fraud: serious crimes against the social order.

Gro Steinsland finds that it is in his capacity as the originator of society that Heimdall comes to function as a unifying figure for the entire cosmological narrative in Völuspá.

Speculation on Function and Origin

Heimdall's enigmatic appearance in the myths has given rise to many different theories about his function in mythology and religion and about his origins. Unlike the gods, for whom there are almost no surviving sources, Heimdall appears in many places, but it is difficult to place him in a clear category.

Various scholars have suggested that he was a goat god, ram god, woodpecker god, sun god, moon god, phallic god, personification of the world tree, a Nordic variant of the Christian figures Michael, Gabriel or Christ, or of the Roman Janus, the Indian Agni and the Persian Mithras.

The historian Georges Dumézil considered Heimdall to be an ancient Indo-European god, of a type he described as the first god. This type, in his description, is not the same as the supreme god.

In Roman mythology, Dumézil found a parallel in the god Janus. In addition, he also described Heimdall as a framework god, i.e. one who is there from the beginning and who will continue to be there until the end.

Dumézil suggested that the Hindu counterpart was the god Dyaus, one of the eight Vasus who reincarnated as the framework hero Bhishma in the Mahabharata; he was a king's son who, along with his seven brothers, had been born of the river Ganges, which had taken the form of a mortal woman.

The seven brothers returned to their immortal form when their children drowned them immediately after birth. Only Dyaus was allowed to live a full earthly life in the form of Bhishma.

His fate was that he himself would never attain power or have direct descendants. Instead, he must act as guardian to his half-brother's descendants, including the five Pandava brothers who represented the social classes. Bhishma himself is the last to die in the Kurukshetra battle.

Branston (1980), contrary to Dumézil, has suggested that Heimdall is a parallel to the Vedic Agni, the god of fire. According to the Vedic texts, he is either born of fire or hides in it, and he is born of either two, seven, nine or ten mothers (the number varies from text to text). The ten mothers are sometimes explained as the ten fingers of the hand that can be used to create fire.

This theory corresponds with, among others, Viktor Rydberg's theories on Heimdall. Others, including the Swedish religious scholar Folke Ström, believe that he should be interpreted as a personification of the cosmic order, including the social order and social classes in the human world.

Still others have seen similarities between Heimdall's characteristics and those of deities in Sami, Tungus and Inuit mythologies. Anders Bæksted suggests that he may be an ancient sun god.

He bases this interpretation on the assumption that his birth of the nine mothers may be an image of the sunrise over the sea, and that it may explain the meaning of his name "He who shines over the world".

However, Bæksted acknowledges that his relationship to the earth militates against this interpretation. He concludes that Heimdall has been a personification of the cosmos with strong relations to the world axis Yggdrasil, the Bifrost and the firmament.

Cosmological meaning

In the short version of the Völuspá from the Hauksbók, a figure appears at the end (verse 65), which is called the Supreme Deity. He is said to dwell in heaven, and to be the god of both beginning and end, that is, to encircle the whole course of the world.

The name of the mighty god who will come to reign after the ascension of the new earth is nowhere mentioned, but Gro Steinsland believes by his choice of words and motives that he can be related to Heimdall.

Heimdall is the only Norse god whose dwelling, Himinbjörg, is celestial. It is from here that he watches over the whole world. Hyndlaljód (verse 44) suggests the same.

In addition, he has an important eschatological role, heralding Ragnarok by blowing the Gjallerhorn; this may be a parallel to the Christian archangel Gabriel. His origins make him special.

Unlike the other gods, as the child of nine women, he is unmixed and complete and not ambiguous.

Since he emerged from a female collective alone, this means that he was not the result of a mixture between different and opposing forces, but the female creative power alone. Steinsland then suggests that Heimdall's cosmological role may be an expression of a pagan reaction to the Christians' preaching of an omnipotent creator God.

Archaeological Sources

Very few archaeological remains are known to be associated with Heimdall. It is generally agreed that Heimdlal is the one depicted with a horn on a panel of the Gosforth Cross from England. In addition, it has also been suggested that the man holding a horn and sword on a rune stone from Jurby on the Isle of Man represents Heimdall.