Your Cart is Empty

Menu

-

- Shop by Type

- End of Line Sale Items

- New In

- Viking Gifts Under $40

- Hand Forged Axes

- Silver Viking Jewelry

- Stainless Steel Jewelry

- Cremation Jewelry

- Necklaces and Pendants

- Hand Carved Wooden Pendants

- Kings Chains

- Viking Drinking Horns

- Pendant Chains

- Rings

- Bracelets

- Earrings

- Beard Beads and Beard Rings

- Collectables

- Ceramic Mugs

- Street Wear

- Horn Jewelry

- Bronze and Pewter Jewelry

- Shop by Theme

- Viking Axe

- Celtic Jewelry

- Dragon or Serpent

- Viking Raven

- Wolf / Fenrir

- Rune Jewelry

- Odin Jewelry

- Ram / Goat

- Shieldmaidens / Lagertha

- Sword, Spear or Arrow

- Thor's Hammer / Mjolnir

- Tree of Life / Yggdrasil

- Helm of Awe / Aegishjalmur

- Triquetra or Triskelion

- Valknut / Knot of Slain

- Vegvisir / Viking Compass

- Veles / Bear

- Blogs

- Help

-

- Login

Odin

In Norse mythology, Odin is the husband of Frigg and is considered one of the most prominent gods in ancient Norse religion, he is particularly associated with:

- War,

- Kingship,

- Runic Magic,

- Wisdom,

- Poetry.

Like the other Norse gods, his functions are very complex, and it is difficult to describe precisely his role as a god.

He is often referred to in the sources by other names: frequently the nickname Allfather is used, other times he is called Ygg (the terrible), another name was Jolner, and under that Odin appeared as the god of the Winter Solstice Yuletide.

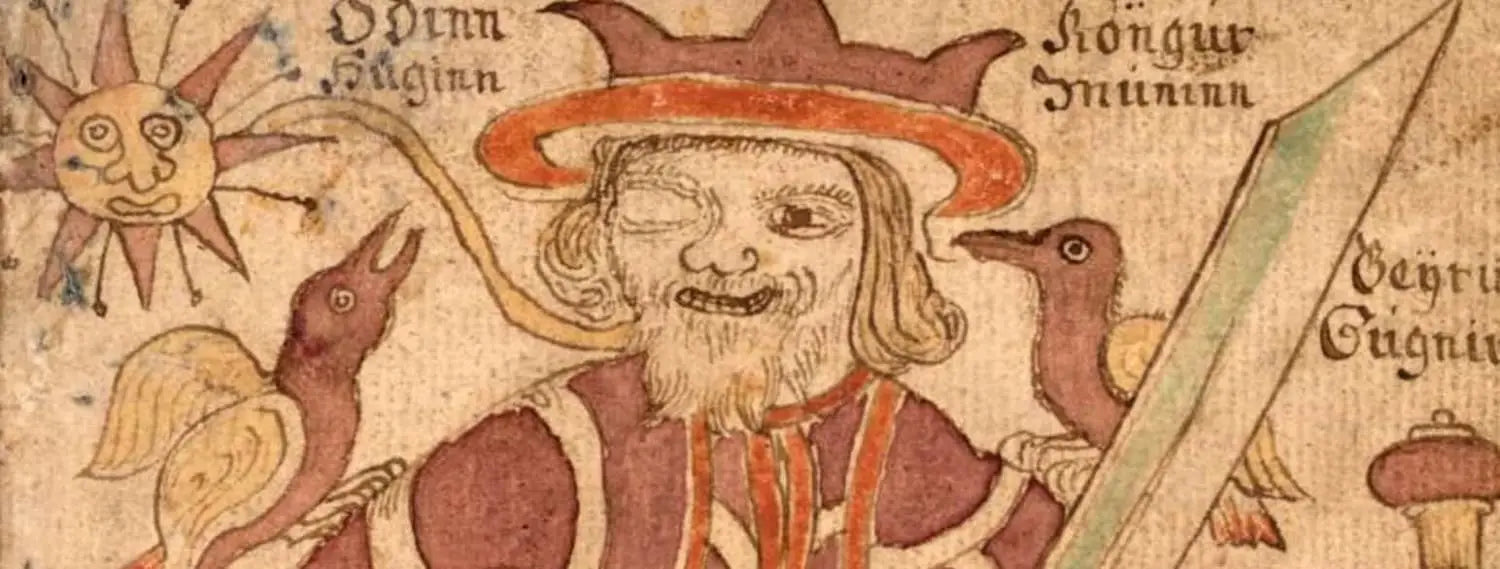

The many names reflect the many functions and roles Odin had. In myths he is often described as a tall, one-eyed, grey-bearded man, and in depictions he is seen riding the eight-legged horse Sleipnir with the spear Gungnir in one hand, followed by the ravens Huginn and Muninn and the wolves Geri and Freki.

Odin was a shapeshifter by nature, he had countless forms and often appeared in disguise, as in one fable from the Old Edda. In the myths he is described as determined to acquire more knowledge and learning, and he often travelled far and wide, either flying like a bird or riding his horse.

Icelandic sources from the Middle Ages describe him as the head of the Aesir. They were the ruling race of gods, and in the Norse world view Odin was the most powerful king.

The limited use of his name in place names compared to Thor and Freyr, for example, suggests that his cult was never very widespread, despite the fact that he was the king of the gods. Other sources show that it was mainly the elite who worshipped him.

Ordinary people would not turn to him, and so few places came to bear his name. In the three cases where we encounter the name Odinkar, for example, it was carried by individuals of noble lineage.

In Norse mythology, the functions of the gods were not necessarily reserved for one deity, for example, Odin was not the only god of war to be worshipped.

The rather milder figure of Tyr was also worshipped. He was mainly venerated by ordinary warriors, while Odin was the god of chiefs and kings, even in war. Another god of war was Thor. His function, however, was largely linked to his role as protector of mankind against destructive and hostile forces.

As a god of war, Odin was not always to be trusted, for even if he had promised victory, he could choose to give it to the opposing side.

Origin

In pre-Christian times he was also worshipped in the rest of the Germanic world, he was known, for example, as Woden in Anglo-Saxon England and Wodan in Germany; this became Wotan, the name under which he appears in Richard Wagner's opera Nibelungen's Ring.

It has been suggested that the worship of Odin may have spread northwards from the Rhine in the 1st century AD and reached Scandinavia along with the cult in the 5th century AD. Here the cult of the Saxons replaced an original fertility cult. Odin appears as a war god in southern Germanic sources from the 5th to the 8th century.

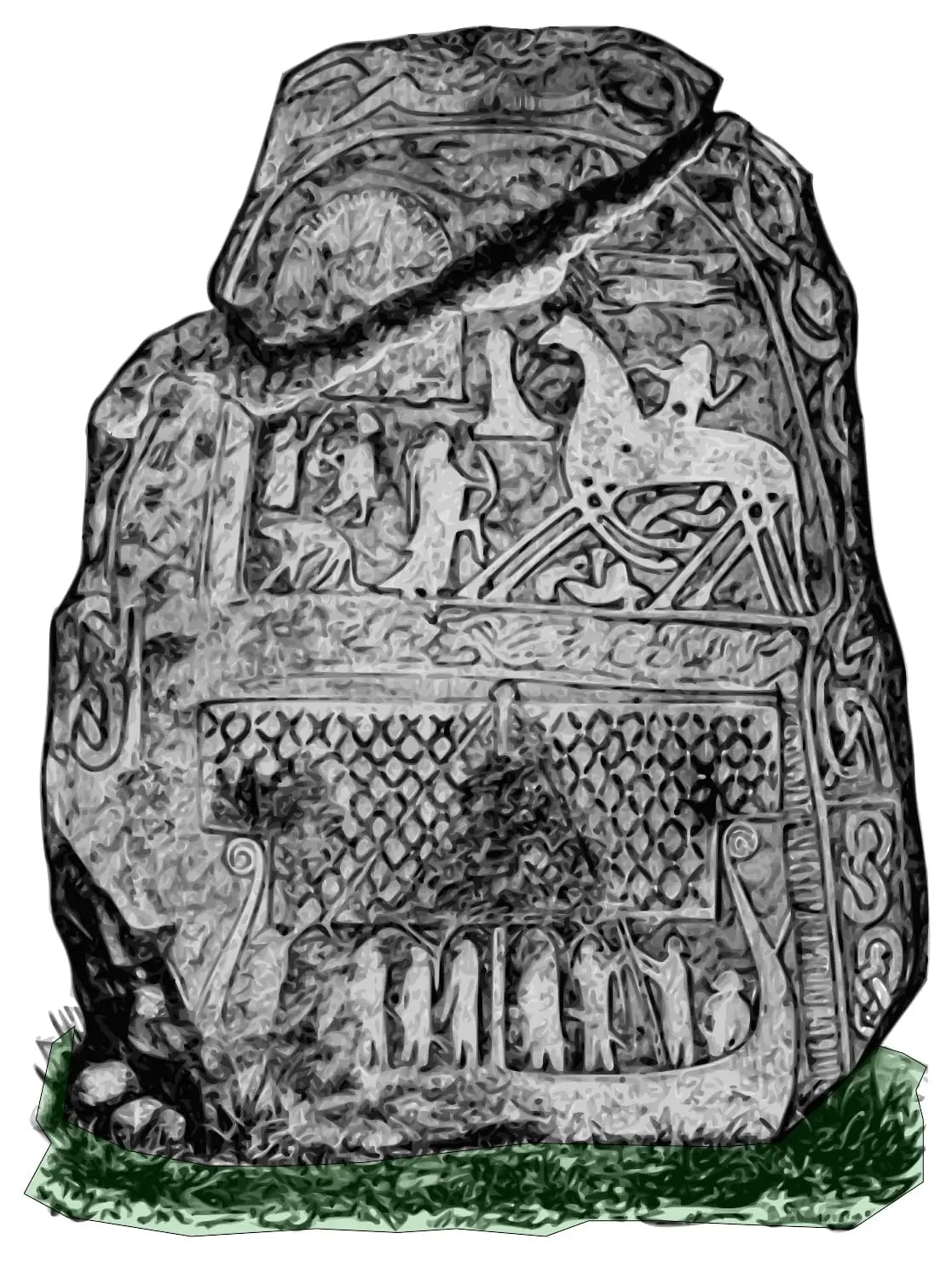

The Scandinavian name Odin evolved from the Old Norse name Wodan during the Germanic Iron Age. Vendel-type handicrafts, jewelry and image stones from the Germanic Iron Age are among the oldest depictions of scenes that can be linked with certainty to the myths we know from the Norse Middle Ages.

Many of the figures on these objects depict Odin. The predominance of portraits of Odin is probably related to the fact that gold objects such as jewelry were so expensive that only the ruling classes could afford them, suggesting that Odin was already the god of the nobles at this time.

It has therefore been suggested that the worship of the Aesir gods headed by Odin at that time replaced an original cult of vanity, as a new social elite emerged as a result of the events known today as the Migration Period.

Other sources suggest that the worship of Odin began long before. The Roman author Tacitus, who wrote an ethnographic work on Germania around 100 AD, describes a Germanic deity whom he refers to by the Roman name Mercurius; usually interpreted as a Roman translation of Odin, as they were both perceived as psychopompos, "leader of souls (to the realm of the dead)."

Other parallels between them were trade, wisdom and learning, and that they both traveled the heavens by divine means.

The Celtic god Lugus had several parallels to Odin: they were both related to magic and poetry, they were both portrayed with ravens and spears as attributes, and they were both one-eyed.

A likely area where the two cultures could have merged was among the Germanic chatters, who lived in the border area between the Celtic and Germanic regions of present-day Hesse.

Function

Odin had several roles, his original function may well have been that of companion to the dead and god of the dead.

In the youngest sources he consistently appears as a war god, creator god and king of the gods. This development into a god-king is probably linked to the establishment of kingdoms in the Nordic countries.

He was an ancient deity, but also had a particular composite character that reflected the new society.

It is mainly in the transition period between Paganism and Christianity that Odin becomes the all-powerful ''Allfather'' known from the Icelandic scriptures, and was then merging with the Christian god.

Odin also possessed other magical objects; one of them was the spear Gungnir, which could not be stopped when thrown at enemies. Another was the gold ring Draupnir, from which eight identical rings of gold dripped every ninth night.

Despite his role as war god, Odin is rarely described as actively fighting, just as warrior attributes such as strength and courage were never attributed to him, rather, the skills he possessed were strategic cunning and the use of deception.

He had no regard for morality or justice, and people bleated to him before a battle to buy a favourable outcome, not for a glorious victory.

The way to sacrifice to Odin was by hanging and stabbing or throwing spears. From the sagas, for example, several descriptions are known of a particular ritual a commander performed before a battle, as the battle began, a spear was hurled at the enemy, to consecrate them to Odin, this is a repetition of the opening of the first mythological war, which began when Odin threw his spear.

It was perhaps this ritual of dedicating the enemy to Odin that infected the god of death and made him the god of war.

Even when Odin had become god of war and king, he still functioned as god of death. At his stronghold of Valhalla, he gathered the best of mankind's warriors who fell in battle. They were called the Einherjar. They would fight for him and the gods against the giants and chaos forces at Ragnarok.

Like Odin, the Einherjar's destiny was not eternal life, but to fall in the final battle on the day of judgement, until then in a liminal phase between life and their final death.

Valhalla was Odin's way of trying to circumvent the outcome of Ragnarok, and his primary task in the mythological tales was thus to postpone his own inevitable death and the destruction of the world he himself had created.

Valhalla was probably a development of older ideas that the fallen warriors continued their last battle in the burial mound, and that it represented the original realm of death.

Odin was also a god of inspiration, magic and poetry. He gained great wisdom and knowledge of the secrets of the runes when he hung himself from the world tree Yggdrasil.

However, this was only a spiritual death, where he sacrificed himself to himself. In another story, he sacrificed his one eye to drink from the well of Mimir, and for this he also gained immense wisdom.

Role in the myths

In the myths, great emphasis was placed on how Odin acquired his magical powers and how he passed them on. He therefore liked to be on the move, travelling far between the different worlds in search of more knowledge, new magical skills or objects.

He acted like an earthly king when he sat in his high seat of the Hlidskjalf, but at the same time he was erratic, followed only his own goals and could provoke wars as it suited him. In myths, poems and sagas there are many allusions to his deceitful character.

Unlike Thor, Odin therefore also used cunning and magic to overcome his enemies, and did not shy away from deception to gain an advantage for himself.

Odin's great wisdom gave him insight into the fate of the world and magical power, and as king it was his responsibility to prepare the gods for the future and brace for the onslaught of enemies.

Like the other Norse gods, Odin was not immortal; he would fall and die a physical death in the final battle of Ragnarok, when only the children of the gods would survive.

However, he was a creator god when he, along with his two brothers Vile and Ve, created the World from the dead body of the primordial giant Ymir after they killed him. In the role of creator, Odin transformed a pre-existing but hostile world into a livable land.

In Norse cosmology, nature was ultimately associated with death, and therefore highly undesirable - through re-creation, the effectively inevitable death can be postponed.

In several tales, Odin is described as an old grey-bearded wise man and wanderer, wearing a broad-brimmed hat and cloak and holding a long staff.

Often he is also on horseback, and his eight-legged horse Sleipnir can run across land, sky and sea and can take his rider all the way across the Nine Worlds.

When he sits on his high seat in Hlidskjalf, he has two ravens sitting on his shoulders, their names are Huginn and Muninn, meaning Thought and Memory.

They can see every movement in the whole world and hear every sound, therefore nothing can be hidden from them. At his feet lie the two wolves, Geri and Freki, both names mean greedy.

The ravens appear in the later sources as personifications of his thought and mind, but originally they associated themselves with Odin in their capacity as scavengers.

Odin's mythological origins and genealogy are most fully described by the Icelander Snorri Sturluson, who in the Gylfaginning states that he was the son of the giantess Bestla and Borr, and that he had two brothers Vili and Ve.

Thus, from the point of view of the genealogy of patriarchal Norse society, Odin's lineage was different from that of the giants, even though his mother was a giant. Together with his two brothers, he killed the giant Ymir and formed the world from his body.

The killing became a major point of conflict in mythology and determined the relationship between Odin's and Ymir's lineage.

Although the two lineages were in fact very closely related, they became mortal enemies because of Odin's murder of the giants' progenitor.

With the nature goddess Jord, Odin has the son Thor, and with his actual wife Frigg, he has the sons Baldr, Hodr and Hermod. With the giantess Rindr he also has sons Skjold and Vale. With the giantess Grid he has the son Vidar.

His relationship with Freya is unclear, however, her marital status was uncertain and, according to the myths, she was married to Od, he may be identical with Odin.

Sources

The many different written sources in which Odin appears paint a very varied picture of him. Each source is influenced by the author's message and the portrayal of Odin in it reflects this.

But the authors drew inspiration for their version of the god from the multitude of different representations. Odin was not a single god, he could appear in many different guises, had many functions.

The Old Edda is a collection of religious poems based on older pre-Christian material. Some of these poems are known in several versions from various manuscripts, all of which were written down in Iceland during the Middle Ages.

The individual poems focus on different aspects of the work of the gods. Odin was an ambivalent god with many different characteristics, so the Odin we meet in one poem is not necessarily the same as the one we meet in another.

Völuspá is an account of the history of the whole world, both what had happened in the past and what will happen in the future. It also contains a frame story about the vole who tells all this to Odin.

She tells him of his own deeds in the past, the killing of Ymir and his creation of Earth and man that he initiated the first war, his sacrifice of his own eye in the well of Mimir and Baldr, the death of his own son.

She tells of Odin's own fate, how he himself will die, killed by Fenrir, and that Vidar will avenge him. But also that a new World will arise in place of the old, which will perish in the sea of flames. The survivors of the Aesir will then commemorate Odin's deeds.

The Havamal contains a tale of how Odin discovered the runes after being hung from the world tree and stabbed with a spear for nine days and nine nights.

Lokasenna gives a different picture of Odin. The poem tells of a quarrel between Loki and the other gods after the death of Balder. When Loki mocks Gefjon, Odin tries to defend her, which leads to Loki verbally attacking Odin, including alluding to his very unmanly practice of seidr: something that was the domain of women. Frigg ends up having to defend her husband, after which she becomes the target of Loki's taunts.

In Hárbarðsljóð, Odin appears disguised as a ferryman. When his own son Thor comes to the great lake where Odin is, he starts a long argument with the unsuspecting Thor and he refuses to ferry him across.

Around 1080, Adam of Bremen wrote one of the oldest descriptions of pre-Christian religion in the North. Odin is called the Furious One, and a warrior who instils strength in men when they face their enemies.

Saxo Grammaticus, wrote a work on the history of the Danes (Gesta Danorum) in Latin around 1200. It also contains euhemeristic tales of the pre-Christian gods, who are described as cunning magicians. They used their skills and tricks to trick the people of the North into worshipping them as gods.

According to Saxo, Odin and the other Aesir originally came from Byzantium, which was then the seat of the gods (Asgard). However, they had been exiled and stripped of all honours by the Latin gods, as Odin had mocked the king of the gods.

The Aesir then headed north. In this way Saxo portrayed Odin as a pure deceiver, thereby exposing the foolish superstitions of pagans and the worship of creatures who were in reality just ordinary people.

In Saxo's own time, pre-Christian religion had not yet completely disappeared in Denmark, and it was therefore important not to refer to the old gods with respect because of the risk of pagan relapses.

Snorre Sturlasson's Younger Edda is today one of the most important sources for the pre-Christian ideas about Odin and the religious context they were part of. Here we find the fullest versions of the myths, which can serve as explanations for many of the other older sources. In the prologue to the Younger Edda, Snorre presents Odin as a historical person.

Like Saxo, he tells us that Odin once settled in the North, where he led the inhabitants to believe that he was a god. Snorre names Troy as Odin's home, and explains (perhaps with a folk etymology) that the Aesir got their name because they came from Asia.

In his description of Odin and the other Norse gods, Snorre attempts to maintain a scholastically value-neutral style, but his account still cannot hide Odin's divine and great importance to pagan religion, which was still fresh in Snorre's own memory.

In Snorre's tale Gylfaginning, it is revealed how the Earth was created and what Odin's background was. He was the son of Borr and the giantess Bestla and had two brothers Vile and Ve. Together they killed the giant Ymir, the first living creature in the world and the ancestor of the giants.

Snorre thus provided the fullest description of the layout of the Earth; however, it is uncertain how widespread his highly systematic worldview was in pre-Christian times. From the dead body of the giant, Odin and his brothers created the Earth.

Odin himself had many children, and from him descended the family of the Aesir. The three brothers also created humans from two pieces of wood they found at the water's edge; Odin gave them breath and life, Vile gave them understanding and emotions, and Ve gave them hearing and sight. They were called Ash and Embla.

It is Snorre who describes Odin as the one who welcomes the fallen warriors to Valhalla and tells us that Odin's aim was to gather as strong an army as possible before the Battle of Ragnarok. However, he also writes that Freya received half of the dead in her hall Folkvangr.

Snorre's Odin was an ambivalent god; as well as being a king and commander, he was also a magician, and he liked to use deception to achieve his goals. A recurring theme in Snorre's myths was Odin's quest for knowledge and understanding.

For example, the second section of Skaldskaparmal tells the story of his theft of the potion from the giant Suttung, whose daughter Gunlod seduced Odin to get her help.

However, the image of Odin is much more detailed in Snorre's story than the way he was actually perceived in pre-Christian times. He was a multifaceted figure, appearing in many forms and under many names in the sources, and relics of his worship have likewise been marked by great variation.

The change of religion in the Nordic countries was a long process in which Christianity slowly spread, mainly from the top of society and the princes down to the general population.

Among the general population, a widespread belief in Odin and the other pre-Christian gods and mythological creatures continued long after the official Christianisation.

The last battle in Scandinavia in which Odin was celebrated for victory was the Battle of Lena in 1208. The exiled Swedish king Sverker had returned at the head of a large Danish army, and he now faced a much smaller Swedish army led by the new king Erik. It is said that Odin appeared in front of the Swedish lines riding Sleipnir. He then led the Swedish attack and gave them victory.

In the Bagler sagas written down in the 13th century, containing descriptions of events from the first two decades of the same century, the same episode also appears.

It is told here that a one-eyed horseman, wearing a broad-brimmed hat and a blue cloak, asked a blacksmith to shoe his horse. The suspicious blacksmith then asked the stranger where he had been the previous night.

The stranger mentioned places so far away that the blacksmith could not believe him. The stranger also said that he had long been in the north, where he had taken part in several battles, but that he was now on his way to Sweden.

When the horse had been shoed, the stranger rose again and said: "I am Odin" to the stunned blacksmith and rode away. The battle of Lena took place the following day.

In later Scandinavian folklore, Odin was long remembered as the leader of the wild hunt.

In several accounts, the goal of this hunt was apparently to capture and kill a woman. Who she was is not clear, but in many places it was the forest dwelling Huldre.

Worship of Odin

Although according to Icelandic sources Odin is the most prominent deity, there is reason to believe that Odin does not enjoy the same degree of popularity as other gods, for example, relatively few towns are named after him. One of them is probably Odense.

Other gods such as Freyr and Thor are much more strongly represented in the onomastic material, with several instances of town names such as Frostrup and Torsted.

That he has long had a prominent place in the religious imagination can be seen, however, from the fact that the day of the week Wednesday is named after him.

Traditionally, it has been believed that Odin was not worshipped at all in Iceland, because the absence of an aristocracy meant that the segment of the population that normally worshipped Odin did not exist.

The idea is based on Georges Dumezil's tripartite theory, but does not take into account the other aspects of the Odin figure: that he was a changeable character, and therefore the identification of him and his role depended on interpretation.

Gudrun Nordal, however, believes that there is evidence, particularly from grave material, that Odin was also worshipped in Iceland in connection with funerals.

Poetry perhaps functioned as a form of sacrifice to Odin. Poetry was Odin's language, and the poets performed a ritual to him (interpreted on the basis of Snorri's explanation). The performance of poetry could also be a way of dedicating sacrifices to Odin.

It appears from several primary sources that people in the Nordic countries sacrificed to Odin as part of the ceremonies called blót. Adam of Bremen, for example, tells of a great sacrificial feast at the temple in Uppsala, which every nine years brought together worshippers from all over Sweden.

Here both slaves and, as he writes, males of each animal species were hung from the branches of the trees. Thietmar of Merseburg reports similar cult celebrations in Lejre on Zealand.

From the account in Havamal of Odin's own hanging and his nickname, Hangatyr (god of the hanged), it must be assumed that human sacrifices of this type in Viking times and perhaps earlier were associated with Odin.

In the Ynglingesaga there is an account which may also confirm this theory. It tells of the Swedish legendary king Aun, to whom it had been revealed that Odin would prolong his life if he sacrificed one of his sons every ten years.

According to the saga, nine sons lost their lives until the Swedes stopped him, as he was about to sacrifice the tenth and last.

In other contexts, sacrifices were made to Odin in times of crisis, in certain situations, people were also sacrificed. In one famous example, found in both Gautrek's Saga and the Gesta danorum, it was even a king who had to suffer death.

King Vikar was travelling with his men when they got off course, they then drew lots as to who should be sacrificed to Odin for better should. The lot fell on the king, and he was therefore hanged.

The sagas also say that the Swedes had sacrificed two legendary kings, Domalde and Olof Trätälja, to Odin after years of famine. Accounts of wars also suggest that killing enemies in battle was seen as a sacrifice to Odin, several places describe a ritual performed by a commander before battle, in which he dedicated his enemies to Odin.

His erraticness in war, however, was known to all, sometimes he betrayed his favourites, and let them lose a battle and suffer death, for which Lokasenna mocks Odin.

In many sources it appears that sacrifices were dedicated to Odin by a spear, this could be done, for example, by the hanged being hit with a spear, just as when a commander shouted "Odin own you all!" at the enemy army before a battle followed by a spear throw.

Sacrifice to Odin gave access to Valhalla on a par with death on the battlefield, in effect, a funeral pyre and/or a spear thrust into the corpse was surely sufficient for the deceased to come to Odin.

This also applied to women, and several sources refer to actual widow burnings, so that the wife could apparently accompany her husband to Odin's hall.

Spring and early summer, was probably the time when the annual sacrifices to Odin usually took place.

Seidr

Odin is referred to as a great Seidrmaker. Seidr was a shamanistic practice, and shamanism has been widespread throughout North-East Europe, Asia and North America up to modern times.

Ideas of a central world tree parallel to the Norse Yggdrasil are found in several north-eastern European and north Asian cosmologies, where it acted as a link between different worlds.

Many of Odin's characteristics can also be found in other shamanistic cultures, for example, the shaman's main role is to act as a link between the worlds of humans and the gods.

Travelling between worlds enables him to gain knowledge that was otherwise secret, or to meet people who are otherwise dead. Animals are often used as a means of transport on such transcendent journeys.

Odin's hanging and self-sacrifice in the tree where he discovered the runes acted as an initiation, bringing him from a state of ignorance to wisdom.

Painful techniques are common in many cultures when training young shamans, as are notions of the birth and rebirth of the shaman.

It appears from the poem that several people are present during Odin's initiation, they gave him neither food nor drink during the nine days and nights when he hung pierced by a spear.

The hanging initiated him into the lineage of the giants and gave him access to the secret knowledge of the world, he picked up the runes from the earth, i.e. the underworld.

Although he had now become part of his mother's lineage and had been given a share in its knowledge, Odin never reciprocated this gift, instead he killed the giant Ymir and thus renounced his lineage.

In the North, Seidr was described as one of the most powerful of the arts, but was also usually perceived as something feminine.

It was therefore a special ritual technique associated with female priestesses and gods, Freya in particular was attributed these powerful powers.

It meant that male practitioners feminised themselves, which was considered highly degrading in pre-Christian Norse society. A man caught practising Seidr was therefore considered unmanly.

According to myth, it was Freya who first taught the Aesir the art of Seidr. It was therefore particularly linked to the habits. Odin was also linked to this god in other ways, for example both he and the Vanir had power over death, and Freya's otherwise lost husband Od may originally have been Odin.

An important part of the stories about Odin are his birds, the two ravens Huginn and Muninn. In texts and images, Odin's animals functioned as allusions to himself.

They are part of older representations, and appear in Iron Age images. In shamanistic tradition, birds represent the mind of the seer or shaman, who can fly freely over long distances and see far, independently of the body.

Modern Conception

Germanic Neopaganism

Odin, along with the other Norse gods, has become the subject of renewed worship. In the Nordic countries, this revived religion is organised in various Asatru associations, which are recognised religious communities in Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Denmark.

Popular Culture

Odin is a main character in Richard Wagner's opera trilogy, Der Ring des Nibelungen. It led to renewed interest in the Norse gods; initially, portrayals of him were based more on Wagner's ideas than on the older sources. Odin has since appeared in a host of different works including comics, TV films, literature and music.